This week saw the appearance of Ebola virus disease in a Liberian visitor to the United States.

Active transmission here is not expected and public

health authorities have done extensive contract tracing. Fifty individuals who were potentially exposed to the virus are being monitored and a small number are in isolation.

This week saw the appearance of Ebola virus disease in a Liberian visitor to the United States.

Active transmission here is not expected and public

health authorities have done extensive contract tracing. Fifty individuals who were potentially exposed to the virus are being monitored and a small number are in isolation. . . . a growing body of evidence demonstrates that programs dedicated to improving antibiotic use, known as "antibiotic stewardship" programs, can help slow the emergence of resistance while optimizing treatment and minimizing costs. These programs help providers prescribe the right antibiotic for the right amount of time and prevent prescription of antibiotics for non-bacterial infections. It is imperative that such programs become a routine and robust component of healthcare delivery in the United States. (emphasis added)To be fair, the man may have had a bacterial infection at the first hospital visit, in addition to the unsuspected Ebola virus infection. We don't know; it's a matter of his private health record. However, I am reminded of how a physician colleague once described the pervasive inappropriate, and often rushed, use of antibiotics,

It's a common problem. Patients present with vague complaints that are plausibly due to bacterial infection and there is a very low threshold for prescribing antibiotics. The patients often request or insist on it, and it often seems harmless to acquiesce. In fact, many doctors view prescribing them as a protection mechanism in case there is an infection or one develops. It's so common that in many clinics and EDs ceftriaxone is referred to as "vitamin R".Perhaps the antibiotic prescription dimension of the encounter on the 26th is all too understandable.

One can hope that a thorough, transparent investigation and analysis of this entire episode can produce helpful knowledge on how to harden healthcare systems for routine healthcare as well as extraordinary events like this one. In the meantime, the CDC has produced clear guidance for evaluating patients with a history of traveling to epidemic regions.

Acknowledgement: The title is inspired from a Medscape Connect item entitled "The cult of Vitamin R", which no longer appears to be available online.

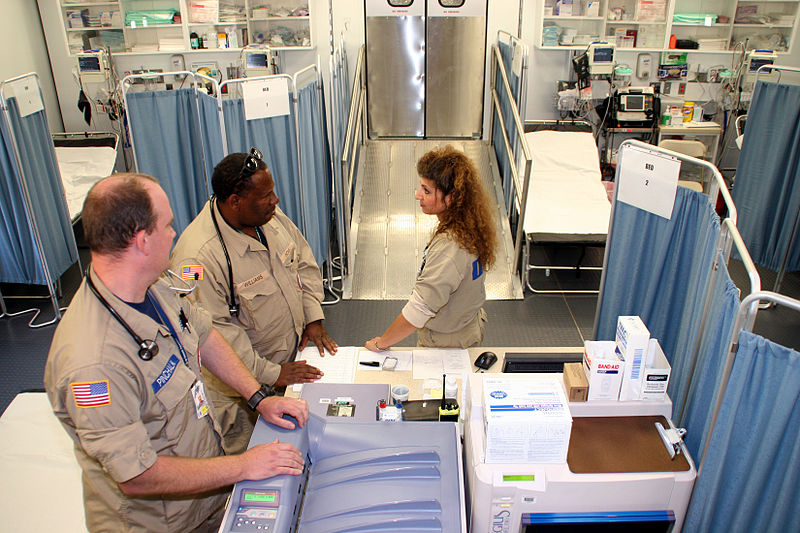

(image source: Wikipedia)

No comments:

Post a Comment