The current Ebola outbreak in Western Africa has been remarkable in terms of the number of cases and deaths; length and geographic extent of the

outbreak; and its designation as a public health emergency of international concern. What could have been done differently to change the

course of events? Thorough analyses of the outbreak and response will be done, and that will

take time, but I think there are several things to consider.

The current Ebola outbreak in Western Africa has been remarkable in terms of the number of cases and deaths; length and geographic extent of the

outbreak; and its designation as a public health emergency of international concern. What could have been done differently to change the

course of events? Thorough analyses of the outbreak and response will be done, and that will

take time, but I think there are several things to consider. More international assistance early in the outbreak. Early intervention is a mantra of modern medicine and public health, and indeed organizations like MSF and others brought impressive resources to bear early in the outbreak. Yet, transmission wasn't controlled and the epidemic grew. More resources are needed urgently. In hindsight, greater multilateral international aid earlier in the outbreak was needed, but how can nations know when NGO efforts need supplemental resources? Perhaps studying the early phases of this outbreak can suggest a way.

Better communication. The social

disruption evident in this event is painfully clear and may have been

intensified by the difficulty of communicating important public health messages. Anecdotes of healthcare workers being attacked and of

disbelief that Ebola virus even exists are but two examples.

Balanced communications in the United States was mixed. On the one hand, many valid messages were circulated, including that Ebola poses little risk to the US general population. On the other hand, one expert told Congress that

We know how to stop Ebola with strict infection control practices, which are already in widespread use in American hospitals, and by stopping it at the source in Africa.

By that calculus, for example, the 2011 outbreak of KPC-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae at the NIH shouldn't have occurred -- and yet the infection control practice in that event was meticulous from the initial presentation of the patient at the facility. What if an Ebola patient isn't recognized immediately when presenting at a US emergency department? And if a case is recognized, is infection control as it is actually carried out in practice likely to be effective? Such questions apply to any nosocomial pathogen, and I think it's important to ask: Given that KPC escaped a patient's room even with full precautions, why not Ebola?

Drug therapy. There are no approved treatments for, or vaccines against, Ebola virus infection. The development of new drugs is a scientifically, economically, and politically complex activity. The urgent need for new antibiotics, for example, has been discussed in connection with a large and growing need. The CDC recently reported that

Each year in the United States, at least 2 million people become infected with bacteria that are resistant to antibiotics and at least 23,000 people die each year as a direct result of these infections. Many more people die from other conditions that were complicated by an antibiotic-resistant infection.That's a massive burden of disease compared to the Ebola outbreak at present. Every case of any infection deserves effective management, but where is the incentive for drug development for Ebola and other exotic, low incidence infections? It is literally taking on act of Congress to help spur new antibiotic drug development in the US. Clearly drug therapies for Ebola would have been beneficial in this outbreak, and how to incentivize development seems an important question. In the absence of effective therapies and drug regimens, misinformation about bogus cures inevitably spreads and requires time and resources to counter.

Certainly these and related issues will be discussed and studied in depth in the coming months and years. Answers to the question of what could we do better next time must be found, because there will be future outbreaks of virulent emerging infections. How will we react?

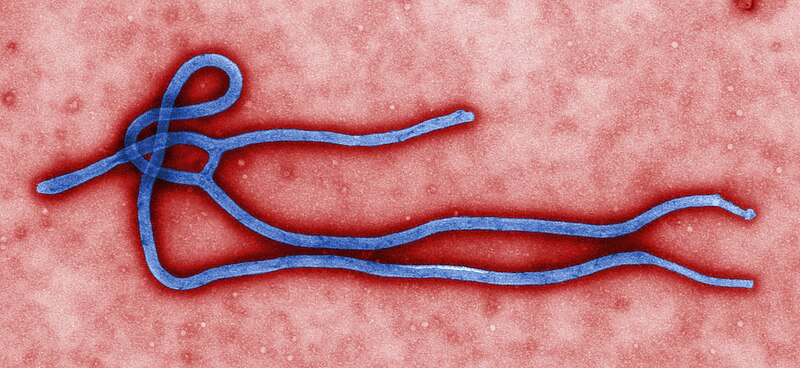

(image source: CDC)