The first confirmed measles death in

the US since 2003 was recorded in Washington State recently, where a

woman died from measles-associated pneumonia. According to a health

department news release, she had an underlying

condition and was taking medications that suppressed her immune system. People undergoing

immunosuppressive therapy are at high risk of

contracting infections and, if they develop infection, often do not exhibit the signs immunocompetent persons show. This woman is thought to have become infected at a medical clinic during a local outbreak; the etiology of her pneumonia wasn't recognized as measles until

autopsy.

The first confirmed measles death in

the US since 2003 was recorded in Washington State recently, where a

woman died from measles-associated pneumonia. According to a health

department news release, she had an underlying

condition and was taking medications that suppressed her immune system. People undergoing

immunosuppressive therapy are at high risk of

contracting infections and, if they develop infection, often do not exhibit the signs immunocompetent persons show. This woman is thought to have become infected at a medical clinic during a local outbreak; the etiology of her pneumonia wasn't recognized as measles until

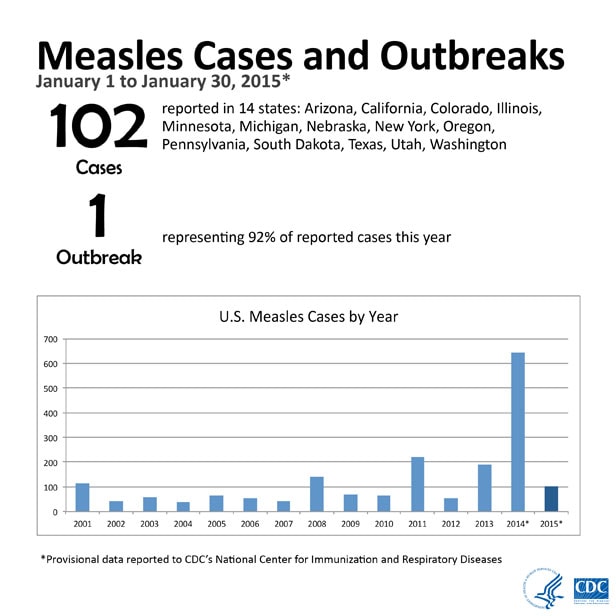

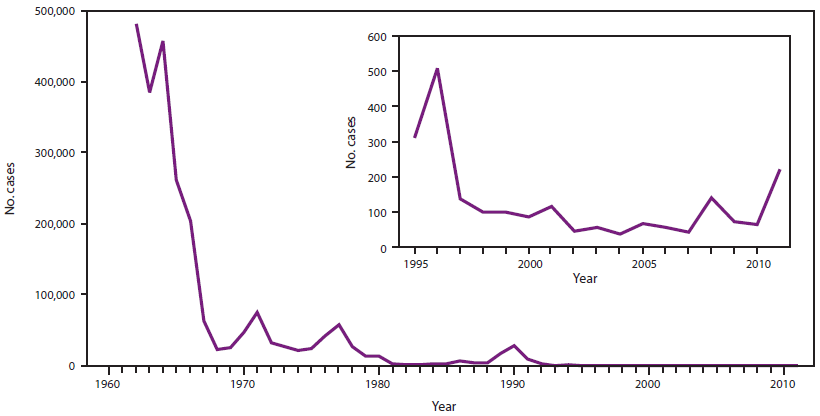

autopsy. In reality, herd immunity is more complex than this. Many complications arise from imperfect vaccine immunity, population heterogeneity (including network effects), uneven vaccination, and those who opt not to receive vaccines. These complexities make it challenging, from a public health practice perspective, to protect populations with vaccines. Nonetheless, this woman's death illustrates how important it is to immunize as many people as possible: Doing so heightens protection of those vulnerable to vaccine preventable infections.

This case has been reported within the context of anti-vaccination notions, or as I prefer to think of it, vaccine skepticism. Regardless of the terminology, there is one simple truth to the incident: She developed what proved to be a fatal infection because someone in her community was not immune to the measles virus. That seems needless when a safe and effective vaccine that conveys long-lived immunity is available. Hopefully laws like those enacted in California and Vermont recently will spread to other states and help to increase the prevalence of vaccine-associated immunity in communities throughout the US.

(image source: Wikipedia)