The multi-state outbreak of measles in the US, which originated at Disneyland theme parks in California, has received much attention in the press recently. Sadly, the event isn't terribly surprising: many people, including children, lack immunity. The reasons for this are varied, and include the MMR vaccine being recommended for children over 12 months of age; persons not completing the recommended vaccination sequence; waning immunity in older persons; and lack of vaccination.

The multi-state outbreak of measles in the US, which originated at Disneyland theme parks in California, has received much attention in the press recently. Sadly, the event isn't terribly surprising: many people, including children, lack immunity. The reasons for this are varied, and include the MMR vaccine being recommended for children over 12 months of age; persons not completing the recommended vaccination sequence; waning immunity in older persons; and lack of vaccination. This latter issue is related to the anti-vaccination movement and this dimension is receiving attention in the media. Some of the discourse is revealing. One example appeared in the New York Times recently, which quoted a Santa Monica pediatrician who has cautioned against the way vaccines are used in the past (but does administer the vaccine in his practice):

“I think whatever risk there is -- and I can’t prove a risk -- is, I think, caused by the timing,” he said, referring to when the shot is administered. “It’s given at a time when kids are more susceptible to environmental impact. Don’t get me wrong; I have no proof that this vaccine causes harm. I just have anecdotal reports from parents who are convinced that their children were harmed by the vaccine.”Perhaps such comments could be rephrased more bluntly: I believe that the vaccine could be dangerous to kids because people who know less about medicine and epidemiology than I do tell me, with great conviction, that they think it's dangerous. Even blunter still might be: The idea that vaccines can be dangerous has a high truthiness, so count me in. Or even, After talking to some patients I've decided to stop worrying about measles and love my unfounded beliefs about vaccination.

I've written before about the importance of understanding those who subscribe to anti-vaccination notions. Statements like this from a physician illustrate how much work has to be done. Several years ago Delgado-Rodríguez and Llorca wrote a very nice continuing professional education paper on bias in epidemiology, which physicians with similar beliefs should read. The following passage is especially important:

Recall bias: if the presence of disease influences the perception of its causes (rumination bias) or the search for exposure to the putative cause (exposure suspicion bias), or in a trial if the patient knows what they receive may influence their answers (participant expectation bias). This bias is more common in case-control studies, in which participants know their diseases, although it can occur in cohort studies (for example, workers who known their exposure to hazardous substances may show a trend to report more the effects related to them), and trials without participants’ blinding.If someone wants to find a cause for a medical event, they will. The plural of "anecdote" is not "data", no matter how convincing the anecdotes may seem.

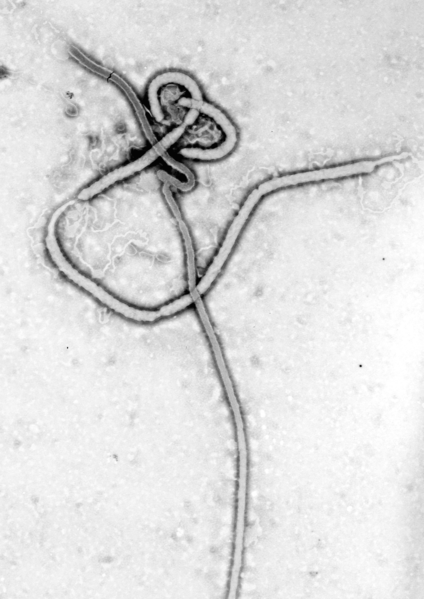

(image source: Wikipedia)